Blog Archives

Celebrating The Sixth Labyrinth with a sale!

March 30, 2016

To celebrate a consequential birthday and the release of this book that has taken so many years to complete, I’m discounting The Sixth Labyrinth for the last week of its pre-order period and a week after. It will go live on April 8, 2016: now through April 15, you can get it for $2.99 (regularly $4.99). Links to pre-order are below the graphic.

Worry not: all of you who have already pre-ordered it will get it for this special price!

Amazon Multi-regional link || iTunes || Kobo || Tolino

Barnes & Noble won’t allow us to set up a pre-order, but Nook readers will still get The Sixth Labyrinth at its sale price after it goes live, through April 15th. HERE is my author page, which will have The Sixth Labyrinth as soon as it’s released. Mark your calendars!

Thank you to my readers!

Biblio: The Sixth Labyrinth & The Moon Casts a Spell

March 15, 2016

- Research for story of Tristan and Isolde taken from:

- Newman, Ernest. The Wagner Operas, 1949

- The world premiere of Tristan und Isolde was in Munich on June 10, 1865.

Partial Bibliography:

- Arnold, Matthew. Tristram and Iseult, 1852

- Auchincloss, Louis. Persons of Consequence: Queen Victoria & Her Circle, 1978

- Auerbach, Nina. Ellen Terry, Player in Her Time, 1987

- Bell, Ian. Dreams of Exile: Robert Louis Stevenson, a biography, 1992

- Bennett, Margaret. Scottish Customs from the Cradle to the Grave, 1992

- Bingham, Caroline. Beyond the Highland Line, 1991

- Brown, Jonathan & Ward, S.B. Village Life in England 1860-1940: A Photographic Record, 1985

- Buchman, Dian Dincin. Herbal Medicine, 1979

- Calder, Angus (Edited by). Robert Louis Stevenson, Selected Poems, 1998

- Cantlie, Hugh. Ancestral Castles of Scotland, 1992

- Carmichael, Alexander. Carmina Gadelica Hymns and Incantations (Collected in the Highlands and Islands of Scotland in the last century), 1992

- Cooper, Derek. Skye, 1970

- Davis, James & Hawke, S.D. London, 1990

- Ewing, Elizabeth. Everyday Dress 1650-1900, 1984

- Fenwick, Hubert. Scottish Baronial Houses, 1986

- Fostor, Vanda. A Visual History of Costume: the 19th Century, 1984

- Fraprie, Frank Roy. Castles and Keeps of Scotland, 1907

- Goldthorpe, Caroline. From Queen to Empress: Victorian Dress 1837-1877, 1988

- Gorsline, Douglas. What People Wore: A Visual History of Dress, 1974, c1952

- Gutman, Robert. Richard Wagner: The Man, His Mind, & His Music, 1972

- Hart, James D (Edited by). Robert Louis Stevenson: From Scotland to Silverado, 1966

- Hawkes, Jacquetta. Dawn of the Gods, 1968

- Hellman, George. The True Stevenson, 1925

- Hendry, J.F. The Penguin Book of Scottish Short Stories, 1970

- Hibbert, Christopher. The Horizon Book of Daily Life in Victorian England, 1975

- Hopman, Ellen Evert. A Druid’s Herbal for the Sacred Earth Year, 1995

- Hunnisett, Jean. Period Costume for Stage & Screen 1800-1909, 1988

- Jackson, Douglas. A Celtic Miscellany, 1951

- Jacobs, Joseph. Celtic Fairy Tales, 1923

- King, Neil. The Victorian Scene, 1985

- Knight, Alanna. Robert Louis Stevenson Treasury, 1985

- Laver, James. Modesty in Dress: An Inquiry into the Fundamentals of Fashion, 1969

- Lister, Margot. Costumes of Everyday Life: An Illustrated History of Working Clothes, from 900-1910, 1972

- Lochhead, Marion. Scottish Tales of Magic and Mystery, 1978

- MacGregor, Geddes. Scotland: an Intimate Portrait, 1980

- Mackie, J.D. A History of Scotland, 1964

- Mackinnon, Roderick. Gaelic, 1971

- Maclean, Charles. The Clan Almanac, 1990

- Mair, Craig. A Star for Seamen, 1978

- Maloney, Elbert S. Chapman Piloting: Seamanship & Small Boat Handling, 1991

- Markale, Jean. Women of the Celts, 1986

- Matthews, Caitlín and John. Ladies of the Lake, 1992

- Maurois, Andre. Disraeli, 1955

- Maxwell, Stuart & Hutchison, Robin. Scottish Costume 1550-1850, 1959 c1958

- McCutchan, Philip. Tall Ships: The Golden Age of Sail, 1976

- McKenna, Terence. Food of the Gods: The search for the Original Tree of Knowledge, 1992

- Moncreiffe and Hicks. The Highland Clans, 1967

- Murphy, Gardner & Kovach, Joseph K. Historical Introduction to Modern Psychology, 1972

- Nicholson, B.E. & Ary, S. & Gregory, M. The Oxford Book of Wildflowers, 1980, c1960

- Norwich, John Julius. Britain’s Heritage, 1983

- O’Brien Educational. Heroic Tales from the Ulster Clyde. 1976

- Pepper, Choral. Walks in Oscar Wilde’s London, 1992

- Plotz, Helen. Poems of Robert Louis Stevenson, 1973

- Prebble, John. Culloden, 1961

- Prebble, John. The Highland Clearances, 1963

- Prebble, John. The Lion in the North, 1971

- Rose, Phyllis. Parallel Lives: Five Victorian Marriages, 1983

- Ross, Anne. The Folklore of the Scottish Highlands, 1976

- Scott, Sir Walter. Manners, Customs, and History of the Highlanders of Scotland, 1893

- Sichel, Marion. History of Children’s Costume, 1983

- Smout, T.C. A History of the Scottish People 1560-1830

- Souden, David. The Victorian Village, 1991

- Swinglehurst, Edmund & Anderson, Janice. Scottish Walks and Legends, 1982

- Thompson, Dorothy. Queen Victoria: The Woman, The Monarchy, The People, 1990

- Tranter, Nigel. Tales & Traditions of Scottish Castles, 1982

- Warrack, Alexander, MA. (Compiled by) Chambers Scots Dictionary, 1911

- Warwick, Christopher. Two Centuries of Royal Weddings, 1980

- Waugh, Nora. Corsets and Crinolines, 1954

- Weintraub, Stanley. Whistler: A Biography, 1974

- Whipple, Addison Beecher Colvin. The Clipper Ships, 1980

- Wilson, A.N. Eminent Victorians, 1989

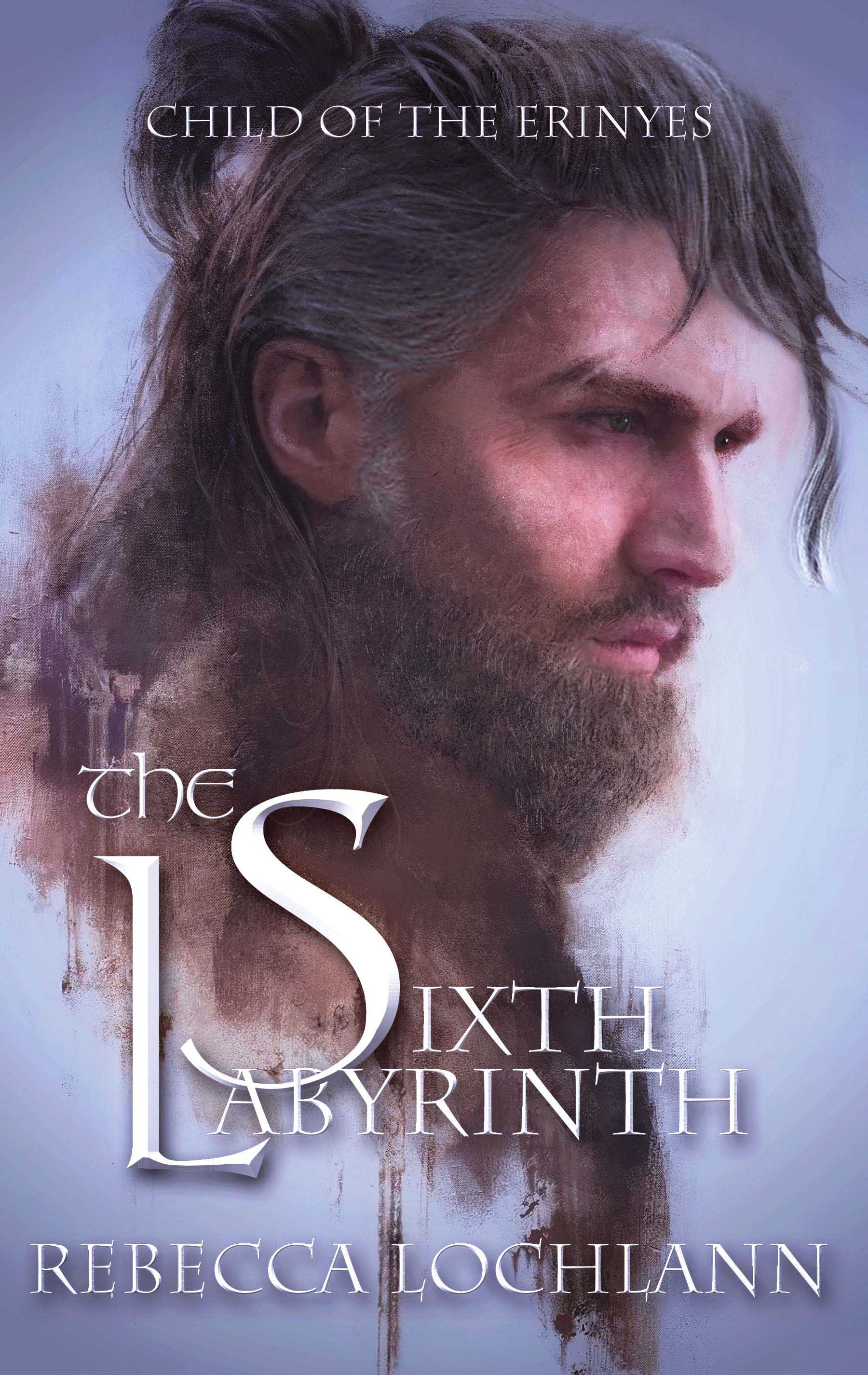

The Sixth Labyrinth (April 8, 2016)

March 15, 2016

Book Five, The Sixth Labyrinth, is live and available at many sites. You can find purchase links in this post below or in the “Links to Purchase” tab.

Update: Paperback version now available!

Athene first clues in Aridela about what will happen in The Thinara King. Aridela doesn’t understand the message then, but she will, in time. Here’s what Athene tells her:

I have lived many lives since the beginning, and so shalt thou. I have been given many names and many faces. So shalt thou, and thou wilt follow me from reverence and worship into obscurity. In an unbroken line wilt thou return, my daughter. Thou shalt be called Eamhair of the sea, who brings them closer, and Shashi, sacrificed to deify man. Thy names are Caparina, Lilith and the sorrowful Morrigan, who drives them far apart. Thou wilt step upon the earth seven times, far into the veiled future. Seven labyrinths shalt thou wander, lost, and thou too wilt forget me. Suffering and despair shall be thy nourishment. Misery shall poison thy blood. Thou wilt breathe the air of slavery for as long as thou art blinded. For thou art the earth, blessed and eternal, yet thou shalt be pierced, defiled, broken, and wounded, even as I have been. Thou wilt generate inexhaustible adoration and contempt. Until these opposites are united, all will strangle within the void.

The Five Sisters of Kintail Image Shutterstock

The Sixth Labyrinth

Book Five, The Child of the Erinyes series. A new myth from Ancient Greece.

![]()

Morrigan Lawton lives a lonely, wearying existence in a land that long ago turned its back on magic and myth.

Curran Ramsay enjoys every advantage and is loved by all who know him. Yet none of his successes can rid him of the sense that he is missing something, or someone. It haunts every moment, awake and in dreams.

Digital version The Sixth Labyrinth

Twenty years ago, the sea stole Aodhàn Mackinnon’s memories. Now a penniless fisherman, his heart reels from an agony he cannot quite remember–until the landowner’s new wife comes to Glenelg.

A silenced but enduring goddess has seen her place in the souls of mortals systematically destroyed.

But she bides her time.

For Athene, thousands of years mean nothing.

Ancient prophecy and the hand of a goddess propel the triad into the winding corridors of The Sixth Labyrinth.

The sea claims final possession,

and leaves nothing behind.

- Links to retail outlets: Click here

Reviews: In the Moon of Asterion

Booksquawk, January 1, 2014, in which In the Moon of Asterion was named, “Squawk of the Year.”

Melissa Conway: In the Moon of Asterion is the third in her excellent Child of the Erinyes series. In my original review of it here on Booksquawk, I wrote, “as a reader, I was captivated, caught up in a boiling whirlpool pulling me toward the inevitable conclusion.” It would be well worth your while to add this historical fantasy fiction to your TBR pile.

It’s difficult to write a review for the third book in a series without touching on plot points in the first two that would amount to spoilers for anyone who hasn’t read them. But if you have read them (and you really should), you’ll understand why I’ve excerpted the following from dictionary.com:

It’s difficult to write a review for the third book in a series without touching on plot points in the first two that would amount to spoilers for anyone who hasn’t read them. But if you have read them (and you really should), you’ll understand why I’ve excerpted the following from dictionary.com:

In The Moon of Asterion may be the grand finale of The Child of the Erinyes trilogy, but as the author points out in the blurb for the first book, “What seems the end is only the beginning.”

The mythological Erinyes are more commonly known as Furies; goddesses of the earth, the incarnation of vengeance on those who have sworn false oaths. From the name of the series alone we expect to read of classically tragic, legendary matters – and Lochlann does not disappoint. However, as it turns out, the scope of the legend is grander than a single trilogy can portray. The first trilogy is set in the Bronze Age, but it’s the first in a series, or perhaps the better description would be to call it a saga that continues through time – eventually to the present day.

In the first three books, our main players are known as Aridela, princess of Crete; Chrysaleon, son of the High King of Mycenae; and Menoetius, his bastard brother. The complicated relationship between them is not that of a mere love triangle – no, the nature of the bond between the brothers makes their situation uniquely bleak, with a divine twist of epic proportions.

Themiste, the prophetess whose job it has been to interpret her own visions and those of others, is given hints throughout the narrative from the goddess Athene regarding the importance of this bond:

Aridela told me she looked first at Menoetius then Chrysaleon, and for one strange instant, she said they merged into each other, and wore each other’s faces. Then the voice said more.

“I have split one into two. Mortal men have burned my shrines and pulled down my statues. Their arrogance has upended the holy ways. I decree that men will resurrect me or the earth will die.”

So much in this book rides on each character making the right choices, and yet, always the wants and desires of humanity assert themselves, leaving them seemingly blind to the big picture. And here is where I begin to verge on giving too much away. I don’t want to spoil the ending with this review; just perhaps prepare the reader for the shocking, yet ultimately satisfying finish. All I can say is that as a reader, I was captivated, caught up in a boiling whirlpool pulling me toward the inevitable conclusion. Now that I’ve reached the end, I can’t wait for the next beginning.

From author, Lucinda Elliot, at her website Sophie De Courcy:

‘The Year God’s Daughter’ and ‘The Thinara King’ were page turners but this is where the real fireworks take place!

You won’t be disappointed with this, the third book, which concludes in a series of shocks that even surpasses the giant shock of the earthquake so brilliantly and terrifyingly depicted in ‘The Thinara King’.

Readers of the earlier books will remember how there are two half-brother rivals from the mainland who aspire to lovely Aridela (the older name for the Ariadne, I’ve discovered), now Queen of ancient, matriarchal Crete – Menoetius, the illegitimate son of the aging King, Idomeneus, dark and serious minded, once so handsome, now left scarred as much internally as externally by the mauling by the lioness, and Chrysaleon, his golden-haired, arrogant heir.

Chrysaleon has won the games and slain the now dead Queen’s consort, earning the right to be her heiress Aridela’s King for a Year. As a mainlander he bitterly resents his impending fate, but fought in the games as he found the thought of any other man winning her unendurable; will he honour his obligation?

Chrysaleon has also won Aridela’s heart – but has her old feeling for her childhood hero Menoetius vanished along with his good looks and his joy in life?

In this book we find out both Menoetius’ and Chrysaleon’s ‘truth’ (the term used by Aridela’s mother) and also the integrity of some of the other characters. Chrysaleon and Meneotius are not the only ones to be tested. Both Themeste and Selene will be tried to the limit, and only one of them holds firm.

One thing is certain, and that is that Alexiare, Chrysaleon’s devoted slave, will stop at nothing to further his interests.

But Aridela’s awful sufferings at the hands of Harpalycus have changed her, just as her taking on the responsibilities of a ruler must, and she is gradually developing a different perspective from that of the careless worshipper of external beauty we met in the first volume.

It is in this volume that the full meaning of the ancient prophecies is revealed – and the terrible implications of Harpalycus’ vaunted immortality.

There are murderous fights, bitter intrigue, and of course, a strong theme of romance running throughout. All the ingredients for an epic story.

If, like me, you are so drawn in that you keep on reading until the small hours, do save the enthralling last section of the book for when you can do justice to the enthralling denouement.

I look forward to reading about the main characters again, in another age.

Reviews at Amazon: read them all

Minos

Minos is a well known title, accepted across the world as the name of a dynasty of kings on Crete. But Robert Graves translates the word “minos” as “Moon-Being,” which suggests it is feminine. Here’s what Graves says in The Greek Myths:

“Minos was a royal title of an Hellenic dynasty which rules Crete in the second millennium, each king ritually marrying the Moon-priestess of Cnossus and taking his title of ‘Moon-being’ from her.” ‘Hellenic’ suggests the term ‘Minos’ relating to a ‘king,’ did not come about until the Hellenic era. It also suggests very strongly that the title belonged to a woman.

Here are several more of his quotes:

(c) Manchester City Galleries; Supplied by The Public Catalogue Foundation https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Edward_John_Poynter_-_The_Vision_of_Endymion,_1902.jpg

“The triumph of Minos, son of Zeus, over his brothers refers to the Dorians’ eventual mastery of Crete, but it was Poseidon to whom Minos sacrificed the bull, which again suggests that the earlier holders of the title ‘Minos’ were Aeolians. Crete had for centuries been a very rich country and in the late eighth century BC was shared between the Achaeans, Dorians, Pelasgians, Cydonians (Aeolians) and in the far west of the island ‘true Cretans’.” This line also suggests that the male “Minos” won the title at a later date.

“Pasiphae and Amphitrite are the same Moon-and-Sea-goddess, and Minos, as the ruler of the Mediterranean, became identified with Poseidon.” Again, the suggestion is that Minos is a later invention, perhaps after an overthrow.

“Zagreus: this myth concerns the annual sacrifice of a boy which took place in ancient Crete: a surrogate for Minos the Bull-king. He reigned for a single day, went through a dance illustrative of the five seasons – lion, goat, horse, serpent, and bull-calf – and was then eaten raw.” The holy Day out of Time, which plays an important role in my books.

Graves also says that “Two or three Minos dynasties may have successively reigned in Cnossus.”

In my story, “Minos” is the title of the High Priestess and holy oracle, Themiste. Minos is a secret title, known only to those initiated into the Cretan Mysteries.

Jacquetta Hawkes theorizes about Crete’s ruling house BEFORE the familiar “King Minos” in Dawn of the Gods:

“In the scenes from the seal-stones, not only is the Goddess always the central figure, being served and honoured in a variety of ways; she is sometimes shown seated on a throne. Supposing that a king did rule as consort of the Goddess, one would expect at the very least that at the royal court, which elsewhere, in Egypt and the Orient, was seen as the human reflection of the divine order, there would have been a throne for the queen as the counterpart of the Goddess. Yet in the sacred throne room at Knossos, and apparently also in the state apartment in the residential quarter, the throne stood single and alone.

If it were not for the tradition of King Minos, and the corresponding absence of any recorded memories of Cretan queens, and perhaps also certain strong if unconscious assumptions among Classical scholars, it seems that the archaeological evidence would have been read as favoring a woman on the ritual throne at Knossos.”

She also says: “In addition to these characteristics, there was another which much more strongly implies the self-confidence of women and therefore their secure position in society. This is the fearless and natural emphasis on sexual life that ran through all religious expression and was made obvious in the provocative dress of both sexes and their easy mingling.”

Kaphtor (Crete)

Psiloritis, Crete https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Psiloritis3(js).jpg

Kaphtor is merely an ancient name for Crete. It comes to us from Egypt mostly.

In his book Unearthing Atlantis, Charles Pellegrino says on page 88:

“When finally the troops entered Canaan, carrying the Ark before them, war broke out almost immediately between the Hebrews and the people they found there. Among those people were the Philistines, whom the Bible tells us came from Caphtor (Crete.) Can it be that the Philistines (Cretan Minoans?) and the armies of Hebrew slaves, having escaped from (or been chased out of) famine-stricken Egypt, were actually two populations of refugees created, in different ways, by the same volcanic catastrophe? Can it be that the present-day conflict between the Palestinians and the Israelis has as its roots Thera and the origin of the Atlantis legend?”

In Minoans, Life in Bronze Age Crete, by Rodney Castleden says on page 21:

“A tablet found far away at Mari in Mesopotamia mentions a weapon adorned with lapis lazuli and gold and describes it as ‘Caphtorite.’ The Egyptians called Crete ‘Kefti’, ‘Keftiu’ or ‘the land of the Keftiu’, while in the Near East Crete was known as ‘Caphtor’: it is as Caphtor that ancient Crete appears in the Old Testament, ‘Caphtorite’ clearly means

Cretan. The similarity of the words ‘Caphtor’, ‘Caphtorite’ and ‘Keftiu’ strongly implies that the Minoans themselves used something like the word ‘Kaftor’ as a name for their homeland.”

on page 37 he says: “There is a tradition that the Philistines originated as Cretans; the Book of Jeremiah (47:4) says, ‘for the Lord will spoil the Philistines, the remnant of the country of Caphtor.’ Caphtor was Crete.”

(Both photos from Wikipedia)

Minos Themiste

Her titles are many: The Moon Incarnate. Moon Being. Most Holy, High Priestess, Seer and Oracle.

And her most secret title: Minos of Kaphtor, which is used only by the fully initiated.

Lilith John Collier https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:John_Collier_-_Lilith.JPG Public Domain

She has magnificent red hair, setting her apart from her countrymen, and she is so beautiful it’s almost scary.

But oracles on Kaphtor (Crete) burn out early, from the smoke, the bull’s blood, the serpent venom and other concoctions they use to see the future.

She has not yet chosen her successor. She knows she should. But she puts it off. Her eye keeps turning to Aridela, who is the subject of so many frightening prophecies, and who has caused her many sleepless nights.

Perhaps if she makes Aridela her heir, that will somehow protect the child.

It’s worth a try.

Iphiboë, Aridela’s sister

Iphiboë is the queen of Crete’s oldest daughter, and heir to that magnificent throne.

Too bad she’s so timid. A shame she’s so afraid of men, of sex.

The vast majority of Crete’s populace believes poor Iphiboë will fail as queen. They believe she’ll be the downfall of their rich, prosperous civilization. If only Aridela were the oldest, is a thought that runs through a thousand minds a day.

Her name means Strength of Oxen. Her father was Valos, who accepted his three golden apples and walked accepting to his own death.

No one knows Iphiboë like Aridela. But not even Aridela knows the full truth of her sister. The nightmares that have plagued her. The premonitions she’s seen. The future she’s endured, night after night in her dreams.

“Salonina Matidia Musei Capitolini MC889 n2” by Marie-Lan Nguyen – Marie-Lan Nguyen (2009). Licensed under Creative Commons Attribution 2.5 via Wikimedia Commons – http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Salonina_Matidia_Musei_Capitolini_MC889_n2.jpg#mediaviewer/File:Salonina_Matidia_Musei_Capitolini_MC889_n2.jpg

Aridela, lunar goddess, mistress of the labyrinth

Photo: Chris Geszvain Shutterstock

At the outset of The Year-god’s Daughter, our Aridela is only ten years old. Yet, fired by divine insight, she enters the bullring, determined to win glory for herself. Because of this act, her life becomes inexorably linked to the lives of two men from Mycenae.

There are two, perhaps three meanings to her name: Utterly Clear, and One Visible from Afar. Robert Graves translates it as The Very Manifest One.

Four words I might use to describe her: “uncomfortable in her skin.”

I will add more about Aridela as books in the series become available.

From Dionysos (Archetypal Image of Indestructible Life), by Carl Kerényi:

“…we may assume that in one aspect of her being Ariadne was a dark goddess. Among the Greeks the epithet “utterly pure” was attached preeminently to Persephone, the queen of the underworld, although other goddesses also were termed hagne. What seems significant here is the intensive contained in the first part of the name. A similarly accented attribute completed Ariadne’s character and provided another aspect. The Cretans also called her “Aridela,” “the utterly clear.” just as they also called Koronis “Aigle.” She could appear “utterly clear” in the heavens. The lunar character of Ariadne can no more be doubted than that of the crow-virgin, mother of Asklepios, who was able to shine like light.”

“Ariadne is described as a girl “with beautiful braids of hair,” an ornamental epithet that Homer confers more often on goddesses than on common girls. According to the Odyssey, (XI 321-22), Ariadne was a daughter of the “evil-plotting Minos,”–an epithet that presupposes the labyrinth as a place of death. Ariadne, the king’s daughter, was mortal, since she was killed by Artemis. She committed the sin of following Theseus, the foreign prince. Homer knew the story of how the hero and his band of seven youths and seven maidens were rescued by means of the famous thread, which is held in the hand in executing the difficult dance figure. The thread was a gift of Ariadne, and it was she who saved Theseus from the labyrinth. Even in this story, which has become so human, Ariadne discloses a close relationship, such as only the Minoan “mistress of the labyrinth” could have had, to both aspects of the labyrinth: the home of the Minotaur and the scene of the winding and unwinding dance. In the legend the Great Goddess has become a king’s daughter, but there can be no doubt as to her identity. In the Greek period of the island she bore a name–although, as we shall soon see, she also had others–that is not a name at all but only an epithet and an indication of her nature. “Ariadne” is a Cretan-Greek form for “Arihagne,” the “utterly pure,” from the adjective adnon for hagnon.”

Carl Kerenyi also says: “Ariadne-Aridela, who had a cult period corresponding to each of her two names, was no doubt the Great Moon Goddess of the Aegean world, but her association with Dionysos shows how much more she was than the moon. The dimensions of the celestial phenomena cannot encompass such a goddess. Just as Dionysos is the archetypal reality of zoë, so Ariadne is the archetypal reality of the bestowal of soul, of what makes a living creature an individual.”

” In the union of two archetypal images, the divine pair Dionysos and Ariadne represent the eternal passage of zoë into and through the genesis of living creatures. This occurs over and over again and is always, uninterruptedly, present. Not only in the Greek religion, but also in the earlier Minoan religion and mythology, zoë takes the masculine form, while the genesis of souls takes the feminine form.”

Valkyrie’s Vigil Edward Robert Hughes https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/5/5e/The_Valkyrie%27s_Vigil.jpg https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_Valkyrie%27s_Vigil.jpg (public domain)

From The Knossos Labyrinth, by Rodney Castleden:

“The princess Ariadne, at once Minos’s daughter and Theseus’s lover, is the mystic, mysterious, feminine heart of Minoan civilization. She is the dark and volatile beauty at the centre of the Labyrinth: princess, priestess, goddess, mistress. She flees from Knossos with Theseus, sailing away at night to meet an ambiguous fate. In some versions of the legend she is abandoned on another island in the Aegean. In some she marries the god Dionysos, in others she commits suicide. Whatever her later fate, she is that heart of Minoan civilization that was borrowed by the growing civilization of the Greek mainland and subsumed by it.”

And finally, Robert Graves says in The Greek Myths:

“‘Ariadne’, which the Greeks understood as ‘Ariagne” (‘very holy’), will have been a title of the Moon-goddess honoured in the dance, and in the bull ring: ‘the high, fruitful Barley-mother’, also called Aridela, ‘the very manifest one’.